The Moment Kitchens Are Actually Tested

Most commercial kitchens do not fail during inspections, test runs, or soft openings.

They fail at a very specific moment — when demand spikes beyond what the layout was quietly designed to handle.

It is the first sold-out banquet.

The unexpected group arrival.

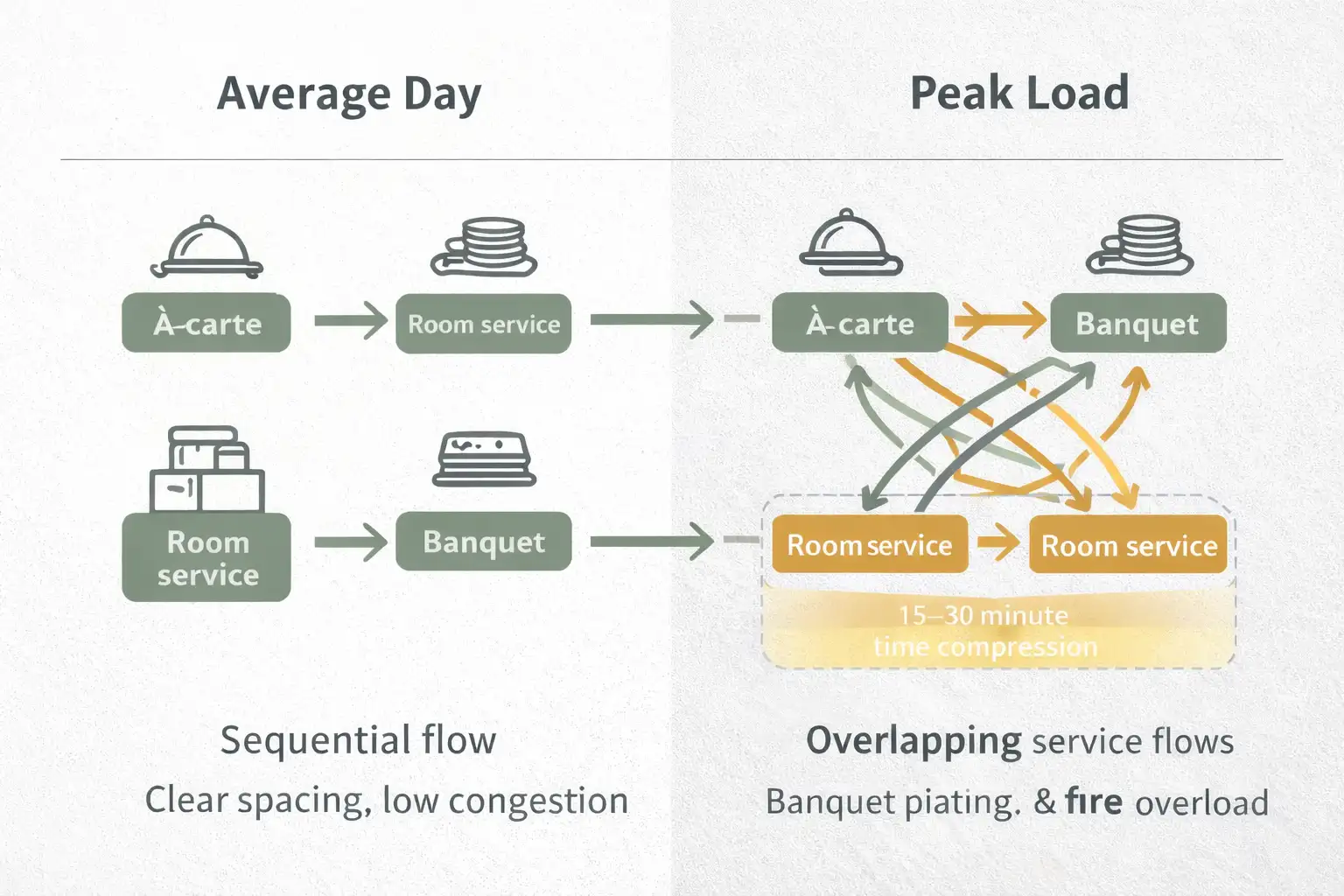

The hour when service lines overlap instead of flowing sequentially.

At that point, equipment is still working, staff is still trained, and drawings are still correct.

Yet performance drops.

Across large hotel and hospitality projects, we repeatedly see the same outcome: kitchens that perform perfectly on routine days begin to fracture under peak load conditions. Not because something is broken — but because peak behavior was never engineered into the system.

This is why kitchens should never be designed for the average day.

They must be designed for the worst 30 minutes.

Average-Day Design Is a Structural Risk

Most kitchens are designed around statistical comfort:

- Average covers

- Typical service rhythm

- Ideal staff distribution

But kitchens are not factories with stable input. They are live systems exposed to:

- Time compression

- Human behavior under stress

- Overlapping service demands

Designing for the average day creates a fragile system. Designing for peak load creates resilience.

What “Peak Load” Really Means in Commercial Kitchens

Most kitchens are designed around averages. Average covers per day. Average cooking cycles. Average staff movement.

Peak load is none of these.

In commercial kitchen operations, peak load means multiple critical processes colliding at the same time.

It is not the busiest day. It is the most compressed moment of that day.

Peak load is defined by:

- Simultaneous cooking cycles reaching maximum heat

- Overlapping plating and dispatch windows

- Zero recovery time between batches

- Staff moving faster, not smarter

A kitchen can perform perfectly for ten hours and still fail in twenty minutes if peak load behavior is not engineered.

Designing for peak load means designing for collision, not capacity.

Two Peak Load Scenarios Kitchens Are Rarely Designed For

Peak Scenario 1 – Banquet Compression

A hotel kitchen prepares:

- 420 covers

- One menu

- One dispatch window

Plating must be completed within 15–18 minutes.

On paper:

- Equipment capacity is sufficient

- Ventilation is approved

- Layout meets standards

In reality:

- Landing zones overload

- Heat builds rapidly

- Staff cross paths

- Plating speed drops after the first 120 plates

The kitchen does not fail because of missing equipment. It fails because time compression was never designed.

Peak Scenario 2 – Overlapping Service Collision

A resort kitchen faces:

- Late breakfast orders

- Early lunch preparation

- Continuous room service

Three services. Three tempos. One space.

During overlap:

- Cooking equipment cycles clash

- Holding areas compete

- Staff prioritization breaks down

Each service works individually. Together, they collapse.

This is not a menu problem. It is a simultaneity problem.

Why the Worst 30 Minutes Define Kitchen Success

Most kitchens are judged by daily output. Successful kitchens are defined by their worst thirty minutes.

These thirty minutes decide:

- Whether food quality holds

- Whether staff stays in control

- Whether recovery is possible

If a kitchen survives its worst thirty minutes:

- The rest of the day stabilizes

- Staff confidence increases

- Management pressure drops

If it fails:

- Shortcuts appear

- Blame replaces structure

- Performance erosion begins

Designing for peak load means designing for this window, not the average day.

“In banquet-driven hotel kitchens, unmanaged peak-load compression typically causes a 12–20% slowdown in plating speed during the most critical service window — even when total daily capacity is technically sufficient.”

Micro Case 1 — Time-Collision Peak (Temporal Load)

Scenario: A hotel kitchen designed for both à la carte dining and banquet service.

On paper:

- Cooking capacity sufficient

- Separate service types defined

- Equipment load approved

In reality:

- À la carte service peaks at 19:00

- Banquet plating begins at 19:15

- Shared hot line equipment reaches simultaneous demand

Observed outcome:

- Cooking cycles overlap

- Holding areas overflow

- Dispatch timing stretches unpredictably

The kitchen did not exceed capacity. It exceeded simultaneity tolerance.

Key insight: Peak load failure here was not about volume — it was about time collision.

Micro Case 2 — Behavioral Density Peak

Scenario: A resort kitchen with correct staff numbers and approved layout.

On paper:

- Adequate aisle widths

- Clear station separation

- Compliance with standards

In reality:

- During peak plating, multiple roles converge at the same pass

- Decision points slow movement

- Staff cluster where visibility and control feel safer

Observed outcome:

- Micro-delays multiply

- Heat and fatigue increase

- Informal shortcuts emerge

Nothing was technically wrong. But behavior density exceeded design tolerance.

Key insight: Peak load is often created by people — not by numbers.

Why Peak Load Failures Are Hard to Detect Early

Peak load problems rarely appear during:

- FAT testing

- Commissioning

- Trial service

They appear only when:

- Pressure is real

- Timing is compressed

- Recovery time disappears

This is why many kitchens look successful at handover — and unstable after opening.

Designing for Peak Load Changes the Questions

Average-day design asks:

- Is the capacity enough?

- Does the layout fit?

Peak-load design asks:

- What happens when two services overlap?

- Where do people naturally slow down?

- Which zones attract congestion under stress?

- How does the kitchen recover after a surge?

These questions are rarely answered by drawings alone.

What a Peak-Ready Kitchen Looks Like

Kitchens engineered for peak load share common characteristics:

- Buffer zones sized for surge, not storage

- Clear priority paths that remain usable under crowding

- Redundancy in critical stations, not everywhere

- Sequencing logic that assumes overlap, not separation

Peak readiness is not about oversizing everything. It is about protecting the moments that matter most.

The Cost of Ignoring Peak Load

When kitchens are not designed for peak conditions:

- Service quality fluctuates

- Staff burnout accelerates

- Management compensates with supervision

- Temporary fixes become permanent behavior

Over time, operational cost rises — even if equipment never changes.

Turnkey Perspective — Why Peak Load Must Be Owned

Peak load performance sits between disciplines:

- Layout

- Equipment

- Workflow

- Human behavior

When responsibility is fragmented, peak conditions fall into the gaps.

A turnkey mindset does not just deliver a kitchen. It owns how the kitchen behaves when pressure is highest.

Final Insight

Commercial kitchens do not fail on normal days.

They fail on the days that define reputation, revenue, and recovery.

Designing for peak load is not pessimism. It is professional realism.

When kitchens are engineered for the worst hour — every other hour becomes easier.

FAQ – Designing for Peak Load

Is peak load only about maximum covers?

No. It is about time compression, concurrency, and behavior density.

Can peak load be solved with more equipment?

Rarely. It is usually a layout and workflow issue.

Why don’t consultants catch this during design?

Because peak behavior is dynamic and difficult to represent on static drawings.

Can an existing kitchen be adapted for peak load?

Yes, but it requires workflow analysis and selective intervention.

Who should request peak-load validation?

Owners, GMs, and operations leaders — before performance problems appear.