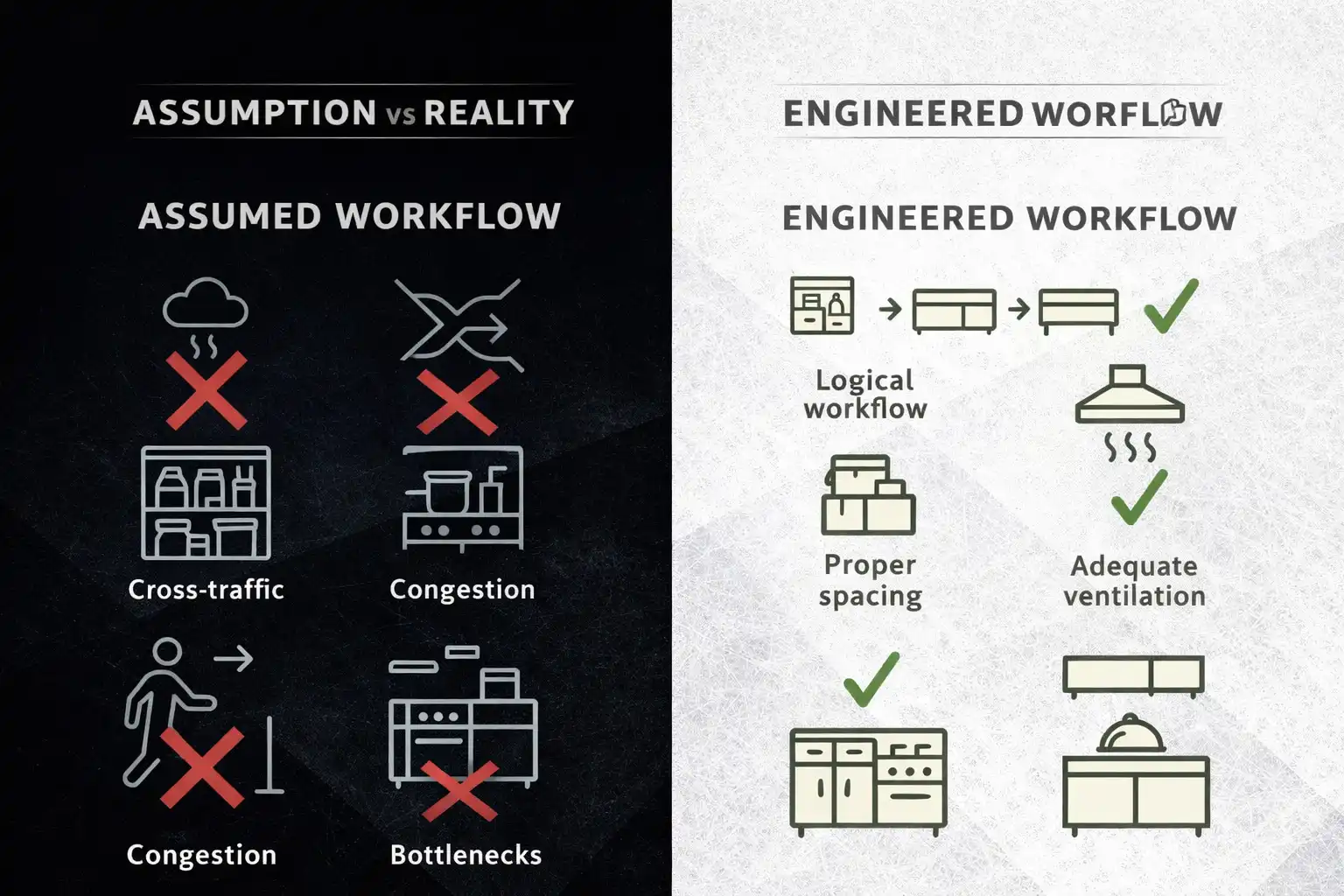

Assumption vs Reality in Commercial Kitchen Performance

Design assumption: Once the right equipment is selected, approved, delivered, and commissioned, the kitchen will perform as planned.

Operational reality: Equipment works exactly as specified — yet service slows, staff struggles, costs rise, and performance drops.

Everything is approved. The equipment is correct. The investment is made.

Still, the kitchen fails.

Across turnkey commercial kitchen projects in Africa, the Middle East, and Europe, this situation repeats itself with uncomfortable consistency. Owners question ROI. Hotel GMs face operational pressure. Procurement teams defend correct specifications. Yet the problem is rarely the equipment itself.

Commercial kitchens do not fail because of wrong equipment. They fail because no one designs how the right equipment will actually be used.

Right Equipment ≠ Working Kitchen

In project environments, equipment is treated as the final goal. In real operations, equipment is only a tool.

A kitchen is not a collection of machines. It is a behavior system.

Equipment specifications confirm capacity. Drawings confirm placement. Commissioning confirms functionality.

None of these confirm:

- How staff will move under pressure

- How tasks overlap during peak service

- How timing conflicts build friction

- How shortcuts appear after opening

When equipment selection is disconnected from workflow behavior, kitchens fail quietly — after handover, not before.

The Silent Failure Pattern Owners Rarely See

Most kitchen failures do not happen during testing or inspection. They happen during repetition.

The first banquet. The third service. The tenth busy night.

Performance erosion is gradual:

- Service rhythm slows

- Staff fatigue increases

- Supervision intensifies

- Temporary fixes become standard practice

Nothing is technically broken. Yet nothing works smoothly.

This is the most dangerous failure type — because it appears operational, not structural.

Five Reasons Kitchens Fail Even With the Right Equipment

1️⃣ Workflow Was Never Engineered — Only Assumed

Layouts show where equipment sits. They rarely show how people move.

When real service begins:

- Crossing paths multiply

- Bottlenecks appear at peak minutes

- Staff adapts with unsafe shortcuts

The kitchen survives — but never stabilizes.

Mini case: In a 350-key city hotel, the kitchen passed all tests but collapsed during the first 800-pax banquet. The layout was optimized for à la carte flow, not simultaneous plating. Result: 18-minute dispatch delay and cold plates.

2️⃣ Menu Timing Was Designed on Paper, Not in Reality

Menus are approved dish by dish. Service happens minute by minute.

During peak operations:

- Multiple cooking processes collide

- Equipment cycles overlap unintentionally

- Holding, plating, and dispatch fight for space

The menu works. The timing does not.

Mini case: A resort kitchen installed premium cooking equipment, but landing zones were undersized. Chefs started stacking trays on prep tables, creating cross-traffic and hygiene risk.

3️⃣ Responsibility Ends at Handover

After commissioning:

- Designers step back

- Suppliers close scope

- Contractors exit site

Operations inherits a system no one fully owns.

When performance drops, every party is technically correct — and practically absent.

Mini case: Exhaust volumes met code, but hood grouping ignored simultaneity. During grill + fryer peaks, heat migrated to service corridors and slowed staff rotation

4️⃣ Staff Behavior Rewrites the Design

Kitchens do not follow drawings. People do.

Within weeks:

- Equipment is used differently than intended

- Movement patterns change

- Unofficial procedures replace planned ones

If behavior is not anticipated, the kitchen redesigns itself — inefficiently.

Mini case: Heavy equipment was installed before ceiling services. Final connections required partial dismantling, delaying opening by 11 days.

5️⃣ Performance Is Measured Too Late

Most projects measure success at:

- Delivery

- Installation

- Commissioning

Real performance shows up only after:

- Repetition

- Fatigue

- Pressure

By then, fixing issues costs time, morale, and money.

Mini case: All equipment worked individually. Under full service load, power tripped and steam pressure dropped. Fixes cost 3× more post-opening.

Assumption vs Reality — Management Edition

Assumption: The team will adapt. Reality: The team creates workarounds.

Assumption: Equipment capacity equals performance. Reality: Workflow defines output.

Assumption: Approved layouts guarantee efficiency. Reality: Layouts ignore behavioral friction.

Assumption: Operations problems are training issues. Reality: They are system design issues.

Why This Problem Keeps Repeating in Hotel Kitchens

Because commercial kitchens are delivered as projects — but operated as living systems.

Most delivery models stop responsibility at handover. No one owns how the kitchen behaves after opening.

The result:

- Equipment works

- People struggle

- Management compensates

This gap is not technical. It is structural.

Turnkey vs Fragmented Responsibility — A Different Perspective

This is not about doing everything under one contract.

It is about owning what happens after everything is running.

Fragmented models:

- Each party protects its scope

- Problems surface late

- Responsibility dissolves

Turnkey mindset:

- Workflow is engineered

- Behavior is anticipated

- Performance is owned

Turnkey is not about control. It is about accountability for outcomes.

What a Working Kitchen Actually Looks Like

High-performing kitchens share common traits:

- Layout supports movement, not just placement

- Menu timing is tested under pressure

- Staff behavior is anticipated, not blamed

- Performance is monitored after opening

The equipment does not change. The system does.

Final Insight

Commercial kitchens do not fail because equipment is wrong.

They fail because behavior, timing, and responsibility were never designed.

When equipment selection is supported by workflow engineering and post-opening

FAQ – Why Kitchens Fail Despite Correct Equipment

If equipment is correct, why does performance drop?

Because performance depends on workflow behavior, not technical capacity alone.

Is this an operations problem or a design problem?

It is a system design problem that shows up during operations.

Can this be fixed after opening?

Yes — but at higher cost and with operational disruption.

Who should own kitchen performance after handover?

The party responsible for aligning layout, workflow, and real service behavior.

How can owners prevent this failure pattern?

By requesting layout and workflow validation — not just equipment approval.